Wow. Do I love BELLWORK™.

FYI: The Bellwork website is currently down as the company tries to navigate from being one that supplied Bellwork workbooks for students to a company that does the same thing in a digtial format. Until then, just know that the Bellwork concept is simple: start the day/period with a chance to practice some of the stuff you've been learning. Math, Written Language, Social Studies, whatever. 4 or 5 questions students answer independently. Bottom line, I'm a fan.

It's quick. It's easy to do. It boosts student achievement. And it helps to create a classroom culture in which every student begins the day on-task. What's not to love about that.

This page is devoted to strategies that not only make BELLWORK™ fun and easy for you but also more effective for your students.

If you have your own little tricks for getting the most out of BELLWORK™, please send them in. I'll create a tab for displaying teacher suggestions and add your ideas to what I hope will be a slowly growing collection of ideas.

- Overview

- Starting

- Stopping

- Checking

- Recording

- BELLWORK

BELLWORK™

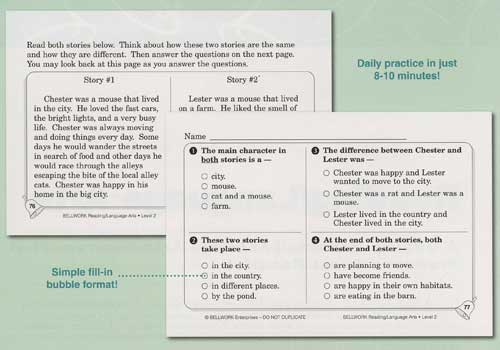

If you're not familiar with BELLWORK™, just click on the last tab. You'll find a bit of general information about BELLWORK™ along with a sample of what it looks like. (Although the sample comes from the Reading/Language Arts program, there are BELLWORK™ activities for math, history-social studies, science, and writing. You can also find assessment activities which are fabulous for test prep.)

If you are familiar with the program, you'll also know that there are several management issues which, when handled successfully, can make BELLWORK™ an almost automatic exercise. The key elements are:

- Getting everyone to begin on time.

- Keeping track of how long they have to complete the work.

- Checking the answers when the time is up.

- Collecting or recording individual scores. (optional)

I'll deal with each of these separately so that, before too long, your own BELLWORK™ activity will be both easy and effective.

Just click on the tab above labeled Starting to find out the secret to getting every student on-task quickly.

GETTING STARTED

As I mentioned on the main page, one of the benefits of BELLWORK is that it helps to create a classroom culture in which every student quickly gets on-task. That's not to say, however, that getting everyone on-task is something that is just going to happen on its own. It's a behavior that needs to be encouraged and supported in order for it to come to fruition. After all, you can't expect to find a beautiful garden in your backyard merely because you happened to throw a handful of seeds on the ground a month ago. The garden will be the result of the time you took to prepare the soil and water the seeds until they sprouted and began to grow, not to mention the patient care at weeding and tending the little seedlings until they were strong enough to be left more or less on their own. It was this effort on your part that produced, within a month's time, a backyard that is in full bloom and bursting with vitality.

Okay, Rick. How'd we get from BELLWORK to Gardening Weekly?

Analogies aside, getting students on-task quickly will take a bit of time and effort on your part. This is partly due to the fact that, when it comes to initiating lesson-engagement, students have become conditioned to the fact that the teacher will do most of the heavy lifting. (It's also partly due to the fact that some students are more than happy to do as little as possible.) They'll sit back and wait, complaisant in this knowledge: when push comes to the shove, the teacher can almost always be counted on to provide a hearty heave-ho.

This Old School culture, in which the teacher directs student behavior, has been around forever. In fact, most teachers learned it when they were students themselves. It's something that is subconsciously absorbed by students until it becomes assimilated, without question, as the operant standard.

Immanuel Kant, the 18th century German philosopher, addressed this phenomenon when he issued what is known as the Categorical Imperative.

Unfortunately, this universally-embraced, Old School mindset is based, primarily, on a culture of obedience brought about through coercion. Do what I ask or I'm going to raise my voice, get angry, or threaten consequences. The downside, though, is that coercive strategies only produce short-term results. Consequently, the teacher is going to have to employ these kinds of strong-armed tactics with a fatiguing and seemingly endless regularity.

Equally culpable in the perpetuation of this universally-embraced mess are the students who, out of sheer self-preservation, respond to the aversive techniques. Their eventual surrender to the relentless and rapidly escalating display of teacher authority merely reinforces the teacher's perception that coercion is an effective teaching tool which, in turn, leads to more of the same coercion. Sadly, though, the higher the frequency that these types of strategies are used, the more the students become dependent upon them. The greater the dependence, the greater the need for the teacher to engage in coercion.

And so it's gone for years and years.

End result? Frustrated teachers and checked-out students.

In order to avoid this all-too-predictable culture from taking over your classroom, you have to ask yourself a simple question.

If it's obedience you want, then so be it. Just be prepared to always be the one to control and direct your students' behavior. Be prepared for them to fight, resist, drag their feet, and willfully ignore the BELLWORK activity you want them to complete. Be prepared to threaten, raise your voice, and get emotional in an endless, not-very-rewarding campaign to bring the students to their knees. And be prepared, by the way, to do this all year long.

If, however, you'd rather have your students develop the ability to direct their own behavior, then you're going to have to create a classroom culture that promotes independence. And what should you be prepared for?

Most significantly, you'll need to be prepared for the fact that independence takes a bit of time to develop. That's because independence--as opposed to obedience--is a long-term, eyes-on-the-horizon, anticipate-a-better-future-for-you-and-your-students kind of thing. It's more crockpot than microwave. Nonetheless, the meal that awaits you is so much more satisfying.

And that's one of the main reasons I love BELLWORK: it helps to support a culture of independent action on the part of the students. As opposed to the students beginning BELLWORK because their teacher is telling them to, my students learned to tell themselves to begin. This Shared Ownership--the term I use for the cultural shift from an Old School top-down, teacher-directed management style to one that is more student-directed--requires two simple steps.

The first is your conviction that independence is worth cultivating. And this belief, it should be noted, is not something I can give you. (Ironic, no?) The attitude that independence is preferable to obedience is something you have to provide yourself.

The second step, which I can provide, is a simple, yet playful cuing strategy I created to alert my students to the fact that they needed to get ready for BELLWORK. Put those two things together--along with a little patience, a bit of grace, and a big helping of trust--and you've got a recipe for success.

![]()

Using a Song as a Cue

Simply put, I played a short song as a way to indicate the impending approach of BELLWORK. More specifically, it was the first twenty-six seconds of the Cagney & Lacey theme song.

Even though the activity we were about to do is called BELLWORK, I've learned that using the school bell as the cue to begin BELLWORK is somewhat problematic.

For one, the bell cannot always be heard in every classroom. This is something I experienced firsthand in my own room. I don't know whether it was the location of our classroom--the far corner of the campus--or the music that had been blasting through our sound system prior to the start of the day. Whatever the cause, the bell was not a reliable cue. And if something is not reliable, you can't really use it to condition your students. Conditioning requires consistency and the sound of the bell was just not consistent enough to get the job done.

The other problem with using the bell as a cue is that it doesn't provide any time to transition from what the students had been doing to what they needed to do. It was just.....rrrrrriiiiiiinnnnnnnggggggg!.....and that was it.

Let's stop for a second to ponder this daily occurrence. Close your eyes and visualize your classroom at the moment the bell finishes ringing. Are you picturing everyone in his seat ready to go? I'm guessing, "Not bloody likely."

Even if you met your class in the morning on the playground and walked them to your room or greeted your third period students at the door as they came into the classroom, I can't image they'd all go directly to their seats and become attentive. That's not how humans behave. Especially when they are a part of a group. And definitely not when they've been conditioned by countless teachers that they can stall until told what to do.

Granted, some students will be at their seats. Others, though, will be digging through their desks or backpacks. A number of them will be interacting socially. One or two might be with you asking questions or wanting to talk about something that happened the previous day.

Regardless of whatever state each student was in, the bell's ring, due to its short duration, will go largely unnoticed. And if they were supposed to be ready to begin the BELLWORK activity but most of them weren't, the predictable outcome would be for the teacher to crack out some Old School initiation routine.

Teacher:

Alright, class. Take your seats, please. Your BELLWORK activity is on the board. You should already be working on it.

(pausing to check for compliance)

I said, take your seats. Everyone needs to get to work right now.

And away we go, doing what teachers have done for years: slowly but surely creating the Old School culture of obedience.

Let's try using a song as a BELLWORK initiator and see what happens. What have you got to lose? (Actually, you have nothing to lose and everything to gain.)

![]()

The Advantages to Using a Song

There are two big benefits to using a song.

1) You won't have to use your already overused voice to initiate the BELLWORK assignment.

Research indicates that 80% of the talking done in the classroom is done by the teacher. Anything you can do to decrease the amount of words spoken only helps to make the ones you do utter more significant. And to use your voice for something as mundane as directing students to get ready for a lesson only hastens the day your voice becomes all but invisible.

Teacher

Trying to get everyone's attention:

Okay, class. We need to begin today's BELLWORK. Please get out a pencil and your BELLWORK journals for recording your answers. Remember, you only have three minutes to answer all four questions. Everyone ready?Reality: That's what you thought they were hearing. For a lot of them--the ones who were still talking with their neighbors or were going through their backpacks or flipping through their journals--it probably came across like this:

Teacher

Trying to get everyone's attention:

Wah-wah wahh. Wah wah wah wah-wah wah-wah wah wah-wah.......

So instead of the words normally spoken, you play the song. The song, which is a right-brain cue, cuts through all of the verbal clutter in the room and sends a clear message to each student: BELLWORK is about to begin.

2) The length of the song provides a brief bit of time for them to make the transition to being ready.

As I mentioned above, rarely is every student ready to go when you want them to be. Whether its location or behavior, at the beginning of the class you'll have students in a variety of readiness states.

The beauty of using a song, or portion of a song, is that regardless of where they were--desk, closet, classroom library, on the carpet, or at a computer--or what they were doing--reading, talking, wandering around, getting a drink of water, or putting their lunches in the lunch basket--the beginning of the song announced to everyone that the day's BELLWORK task was going to appear in less than thirty seconds. And it was the length of the song (26 seconds) that provided them with enough time to get themselves in the ready position in spite of what each student may have been doing before the song began.

This brief musical interlude became an important part of the on-task process as it provided everyone with enough time--but not too much time--to disengage from one thing and transition to something different. And thus began the transition from obedience to independence. I merely provided the cue to begin the process. It was then up to each student to slowly but surely develop the requisite self-determination necessary to be ready for the actual BELLWORK activity.

![]()

Putting It All Into Practice

Now that we've briefly addressed the rationale for using music as a cue, let's shift our focus to how it actually plays out in the classroom.

Scene: Room 12, Sequoia Elementary School

Time: 8:04 a.m. (One minute before the morning bell was set to ring.)

At this point in the morning, I've got a room full of students. Some of them showed up at 7:30 when they were allowed to enter whereas others were wandering in just before the official start of the day. They're hanging out, talking, reading, organizing their desks, using computers, and basically doing all of the normal things students do at the beginning of a school day.

I've got some kind of up-beat music playing through our cheap but effective sound system.

For the record: Our sound system was nothing more than an old iPod connected to a boom box. The speakers had been detached and placed on top of some cabinets for better sound dispersal. (As opposed to a boom box, you can also connect an iPod to regular computer speakers which, if you look around your school, can usually be found collecting dust somewhere.) Using an iPod as the source of our music--which is described in "How to Use Music for Management" in the book, Eight Great Ideas--makes the selection of songs easier to do. This is a good thing because whenever an effective teaching technique is easy to do, the teacher is more likely to do it. Or, as Einstein famously noted, "Everything should be as simple as possible." And using an iPod--as opposed to the CD shuffle I used to do because I couldn't recall which CD had the song I wanted to play--is about as easy as it gets.

The music's a bit loud, but that's the way we liked it. The endorphins were flowing and everyone, for the most part, appeared to be in a good mood. Or at least awake at this point since it's tough to sleep when the Newsboys are beltin' out "I Am Free."

Time: 8:05 (The bell rings to start the day.)

As soon as I heard the bell, or figured out the bell had rung by the time on the clock, I killed the music. This abrupt end to whatever song had been playing was actually the first part of the cuing system. The sudden absence of the music meant that the pre-morning routine of just hanging out was over and it was time to get on-task.

I then scrolled to the "Get ready for BELLWORK" song and hit play. The distinctive opening notes of the song had everyone immediately thinking the same thing: BELLWORK!

Specifically, the song meant:

1) Take a seat.

2) Find a pencil.

3) Get out your BELLWORK journal.Note: You can have your students write their answers in some type of journal or notebook if you project the activity onto a screen. If you're lucky enough to be using the student books, they'll be able to record their answers in the book itself.

As soon as the song ended, I flipped on the projector. The students, seeing the day's activity on the screen at the front of the room, quickly and quietly got to work.

Thirty seconds into our day, without a single word being spoken, my students had gotten themselves on-task. Add to that the proven academic boost that daily BELLWORK practice provides and you're looking at a combination that's hard to beat.

![]()

THE EASIEST WAY TO STOP

Although you might think that stopping the BELLWORK™ activity could be done with a simple, "Please stop working," there's actually a bit more to it than that.

Reality: If you've read the preceding 2,500 word post on the issue of starting BELLWORK™, you'll know what I mean. I promise, though, that the remaining posts won't be as long. I just felt it was important to share my thoughts regarding the issues of obedience, independence, and the creation of a classroom culture that promotes student success and achievement.

Before addressing the stopping part, though, let's take a quick look at the "during" part.

What You Do During BELLWORK™

As my students started to work on the day's activity, I began to walk around the room assessing their progress. I truly loved those first few minutes of our day. There was that wonderful feeling of students fully engaged in a task; that calm, serene atmosphere of hard work and accomplishment.

I also liked the fact that our BELLWORK™ time presented so many opportunities to provide a gentle pat on the shoulder or to offer a word of appreciation for someone's laser-like focus. They were so intent on the activity that I could drift surreptitiously from place to place without really disturbing anyone.

Equally important was the fact that my wandering afforded the students a chance to ask me a one-on-one question about the day's activity. And if the question was anything other than a slightly veiled attempt to get me to merely provide the answer, I supplied what insight I could.

A lot of the questions, though, were in the category of, "I don't get question #3" to which I responded with, "Do the best you can."

Shared Ownership: The promotion of independence can be done in big ways and small. Doing a child's thinking for him does little to nurture and develop a sense of self-reliance. That's not to say that I wouldn't attempt to clear up any confusion a student may have had regarding a question. It's just that I wanted everyone to understand that, when it came to answering the questions, I'd provide what clarity I could but you had to rely on your own thinking in order to come up with the actual answer.

So, while they worked at completing the BELLWORK™ activity, I answered what questions I could, encouraged those in need of encouragement, and shared my appreciation for a student's attention to the task at hand. And all done in a calm, relaxed fashion.

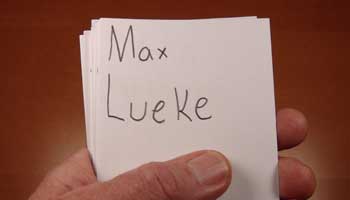

It should be noted that a big part of the serenity and calmness I felt was not just the pure enjoyment of interacting with students who were engaged and on-task. It was also attributable to my trusty little digital timer, Max.

We had a "name the timer" contest when I first brought a timer into the room.

The name, Max, was chosen by the students from all of the submitted entries.

The use of a digital timer to keep track of how long my students have to complete a task is one of the five things I would never teach without. (The other four are sign language, student numbers, sound makers, and a set of Class Cards.)

Here's a passage from the New Management Handbook that addresses this incredibly simple teaching tool.

If I want my students to work on an assignment for 15 minutes, I'll pick up Max, set him for the proper amount of time, and show the class.

Mr. Morris

Showing the students that Max has been set for 15 minutes:

We have 15 minutes for this assignment. Any questions?

Seeing no question hands raised:

All right, then, I've got a question. What are you going to do if you finish early?Suggestion: It's always a good idea to make sure your students are aware of appropriate activities in which they can engage whenever they finish ahead of the time limit you've established. We have an E.T. Chart--Extra Time--that lists suggested activities. By referring to the E.T. Chart, students will find something significant to occupy their extra time.

Mr. Morris

Following up on his question:

That's right. Just check the E.T. Chart, and choose one of the activities listed. Any other questions? No? You may begin.I then press the button on Max which begins the 15 minute countdown. And now that I no longer have to worry about watching the clock, I can completely and freely interact with my students. I set it, forget it, and then go join the students. And guess what? I never have to worry about the time getting away from us. That, you will soon discover, is a major stress reducer.

Fifteen minutes later, Max starst beeping. In our room, that beeping sound means:

Stop what you're doing and get ready for something else.

Consequently, the students put away their materials as I disengage from the students with whom I was interacting. By the time I get back to my desk, a student will have pressed the stop button--usually after a couple of beeps--and we'll be ready to move on to our next activity. Just the fact that I don't have to say, "Please stop what you're doing and get ready for our next activity" is worth the money I spent for Max.

Back to Reality

Anyway, as soon as the song ended and the activity was projected for everyone to see, I pressed Max's start button to begin the three-minute countdown. I then started to wander around the room supervising progress and interacting quietly with individual students.

Note: The more you do BELLWORK™ with your students, the better you'll get at determining appropriate time frames. At first, you'll just be guessing. Before too long, though, you and the students will have figured out how much time they actually need. (Not how much time they might want, mind you, but how much time it should take them to complete the day's task.)

Stopping

Three minutes later--or whatever time frame was appropriate for the task--the timer beeped causing the students to put down their pencils. Without a word being spoken, the students had responded to the "BELLWORK™ is over" signal--an example of student independence--and were ready to move on to the correction portion of the activity.

CHECKING STUDENT WORK

As President Obama is fond of stating: Let me be perfectly clear.

Note: He didn't make the statement about BELLWORK. That was me. The "Let me be perfectly clear" part was his contribution.

Although we'd like to think that our students would give each day's BELLWORK assignment their all, that's not necessarily the case. Some students need to be convinced that their teacher not only expects their best effort but will actually be taking the time to see if such effort was expended.

It's similar to how another president, Ronald Reagan, treated the Russians when he was negotiating nuclear arms reduction treaties. He always expressed his trust in their cooperation. At the same time, though, he insisted on verifying their compliance. The only difference with the classroom setting is that, instead of patting down a student for a WMD, I was merely asking for his score for that day's BELLWORK activity.

Reality: It's one thing to talk about your students doing a good job. It's another thing altogether to do something about it.

Before taking scores, though, you and your students are going to have to identify the correct answer to each question. And that, to me, was the fun part: calling upon students to hear which answer they thought was the correct one. Done in the right way, this teacher/student interaction can be fast-paced and focused. Adding a spark of energy and excitement to the whole process was the randomness of which student was going to be called upon next.

"How is that possible?" you ask.

"With a set of Class Cards," I respond.

![]()

Background Info on Class Cards

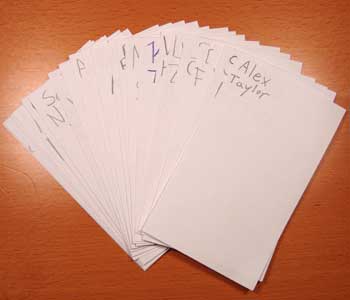

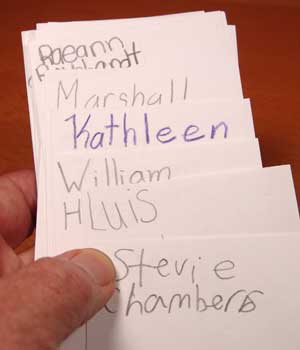

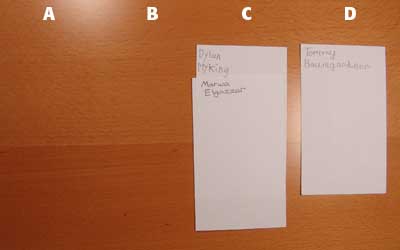

For those of you not familiar with the concept, it's really quite simple. The Class Cards technique, as described in the first book I wrote, is nothing more than a set of 3 x 5 index cards on which I've written the names of my students, one student per card. (In the sample below, the students wrote their own names.)

The cards are shuffled and then held name-side-up in my hand. After that, it's a simple matter of a quick look to see whose card is showing and calling upon that student.

Not Popsicle Sticks

If you're thinking, "Oh, the cards are just like the popsicle sticks I use," I'd like to politely point out that they're not. Although the sticks, like the cards, can be considered a random name generator, there are two advantages to using a set of cards.For one, you'll be able to hold the entire set of cards in one hand with the names of your students already facing you. Consequently, calling upon student after student after student is a snap. The sticks just don't allow that same smooth flow. You've got hold the can in one hand as you draw a stick with the other. You then need to turn the stick so that you can read the name. Granted, it's not a huge difference but, over time, the minor nuisance becomes a major nuisance.

The more significant advantage, though, is the ability to know exactly which students are about to be called upon. This can be done by staggering the top six or seven cards so that the names can be seen.

Seeing who's next enables me to shape the interaction so that the needs of my students are being met.

Popsicle sticks, on the other hand, will leave you with a never-ending sense of uncertainty as to whose stick is about to be pulled from the can. The uncertainty of the draw is not conducive to student achievement as evidenced in this scenario:

A set of cards will eliminate the uncertainty and help you to avoid putting an academically-fragile student in a compromising position.

Take Your Pick

If popsicle sticks are working for you and your students, have at it. If you haven't tried index cards, though, you might want to give 'em a shot. I think you'll be happy you did.

Whether it's cards or sticks, let's pick up where the previous post on "Stopping" left off.

![]()

Three minutes later--or whatever time frame was appropriate for the task--the timer beeped causing the students to put down their pencils. Without a word being spoken, the students had responded to the "BELLWORK™ is over" signal--an example of student independence--and were ready to move on to the correction portion of the activity.

Without a word, I'd take the set of cards in my hand and tap them a coupla' three times on my desk.

This rather distinctive sound sent a clear message to my students: Have an answer ready, please.

Mr. Morris

Looking at the top card in his hand:

Dylan?Note: I didn't have to say more than just his name. That's because my students knew that I expected everyone to be aware of the fact that since we had just begun the correction process, we're talking about question #1. Realistically speaking, though, it might take a week or two before you can get your students to the point where these things become both understood and acted upon.

At first, you might want to actually say, "Question #1" before you begin to call upon them. But only, as I just stated, for a week or two. After that, it's up to each student to stay on top of things so that everyone knows, without any prompting from you, which question is being checked. Just another example of Shared Ownership. Or, stated differently: I'll do my part, you do yours.

Dylan

I think it's "C."

And here's where the fun began.

After hearing Dylan's response, I said, "Thanks."

I didn't repeat his answer.

Note: This Old School behavior is called "Echoing" and is something I encourage teachers to minimize if not eliminate completely. You can read all about this in chapter two of the book, Eight Great Ideas. The chapter is called Confessions of a Former Echoer.

I didn't say, "Yes." I didn't say, "No."

Just a simple, "Thanks."

Or maybe it might have been, "Uh-huh," or "Got it," or a nod of my head. Any one of these responses let the student know that his answer had been received by his teacher.

Whatever the case may be, a short response helps to keep the interaction from getting bogged down by too much teacher talk. After all, we're merely trying to solicit responses in an effort to identify the correct answer which shouldn't require but a word or two from me. This reduction in words enabled me to call upon many students for their answer to the same question which makes the whole thing fast-paced and engaging.

Call On Many Students

How many students should you call upon? It's up to you. However, here's a simple formula:

Here's the same formula shown is a different fashion.

For those of you who are somewhat math-phobic, here's an actual example.

30 students each answered 4 problems. 30 divided by 4 equals 7.5 students. Therefore, you will call upon 7 students for each of 2 problems and 8 students for each of the other 2. This will result in every student being called upon at some point in the correction interaction: a highly desirable occurrence.

And now, with all of the previous thoughts in mind, let's rewind the whole show to the part where I was tapping the cards on my desk.

From the Top

Mr. Morris

Looking at the top card in his hand:

Dylan?Dylan

I think it's C.Mr. Morris

Placing Dylan's card face-up in front of him:

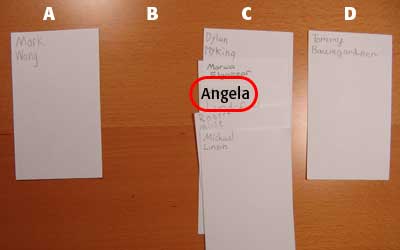

Thanks.Suggestion: I place the cards in piles according to the answer given. Since there are only four possible responses, I know to create four piles. I'll show you why in just a moment.

Mr. Morris

Looking at the next card:

Tommy?Tommy

D.Annoying reality: When the answer possibilities are phonetically similar--B can sound like C which can sound like D--you might want to think about having your students respond with a word instead of a letter. Apple, Box, Chocolate, and Doughnut are less likely to be misunderstood than A, B, C, and D. Not to be overlooked is the entertainment value of hearing students say the word, "doughnut." Or maybe that's just me.

Shared Ownership: You could take suggestions from your students regarding the words to be used for that week. Who knows where that might take you. Vocabulary words? Foreign languages? Student names? The possibilities fairly boggle the mind.

Mr. Morris

Placing Tommy's card in the "D pile" and looking at the next card:

Marwa?Marwa

C.

Marwa's card went in the "C pile" but in such a way that I could still see Dylan's name underneath it.

I kept calling names and placing cards in piles until I've called upon seven or eight students. (I'm using the math sample from above.)

At this point, I'm now ready to confirm the correct answer. And depending upon the question itself, I can do this in one of two ways.

![]()

Confirmation 1: Quick and Easy

The easy way is to just announce the correct answer.

Mr. Morris

If you said or were thinking...

Slight pause:

C...

Another pause:

You're correct.

Mild huzzahs from the correct responders; not much of anything from the students who offered something other than C. And what a pleasant change this was from the Old School models of student engagement in which the teacher stopped taking responses after hearing the correct one.

Pleasant Change #1

I enabled several students to share the correct answer. We didn't stop with the first one that was heard. I merely said, "Thanks," and called upon another student.

Pleasant Change #2

Since everyone quickly learned that I take more than one correct response, we no longer had to put up with five or six students blurting out, "Oh, I was going to say, 'C.' " Instead, they waited patiently, hoping to hear their names called so that they, too, could verbally cast their votes for C.

Pleasant Change #3

It became safer for students to offer an incorrect response. As opposed to an immediate rejection--received in front of their peers--the incorrect response was accepted in the same response-neutral fashion that the correct responses were accepted. However, the students who were incorrect were made aware of their mistake when I announced the correct answer. The fact that they were wrong, though, hadn't been pointed out to everyone.

The Low Affective Filter: The feeling of safety on the part of my students decreased their anxiety at responding which led to a corresponding increase in their individual achievement.

Pleasant Change #4

We didn't get bogged down in dealing with individual responses. Each one received nothing more than a word or two from me.

![]()

Confirmation 2: Making a Point

If I would like to use the question as a teaching point, I don't just announce the correct answer after calling upon many students. Instead, I call upon one of the students who gave me the correct answer and have them explain why they chose that answer.

And that's the main reason I made the effort to place the cards in piles according to the response. I wanted to know which students had responded with the correct answer and should, therefore, be able to shed some light as to how they solved the problem.

Mr. Morris

Looking at the five cards in C pile:

Angela, you said C. Why?

Angela

Well, I've learned that when you want to find the average, you have to add the numbers together and divide the total by how many numbers you had.Mr. Morris

Well said.

Looking at the card in the A pile:

Mark, what was the correct answer again?Mark

It was C, Mr. MorrisMr. Morris

Thanks, buddy.

And on to the next question and the next and the next. Drawing cards, calling upon students, placing the cards in piles, and confirming answers. Done quickly and with a minimal amount of teacher talk, the entire assignment can be dealt with in a matter of a minute or two depending upon how many of the questions you turned into teaching opportunities.

![]()

One More Step

The only thing left to do is collect scores. You'll find a couple of suggestions by clicking on the next tab at the top of this page.

![]()

RECORDING SCORES

As with most things in the classroom, there are several ways you could accomplish this task. It merely depends upon what's most important to you.

Quality

How accurate are the scores being recorded and how many are you recording?Effort

How much effort do you want to expend in recording scores?Time

How long do you want the recording process to take?

Basically, you get to choose two of the three factors. In other words:

> You can get scores from everyone with minimal effort but it's going to take time.

> You can get scores with little effort in a short time but you won't be able to get everyone's score.

> You can get scores from everyone quickly but it requires extra effort on your part.

With that established, allow me to offer some suggestions.

![]()

One of the easiest ways to record scores is to have your students provide them to you. This can be done in one of two ways.

One of the easiest ways to record scores is to have your students provide them to you. This can be done in one of two ways.

Personal Visit

As soon as you've finished correcting the assignment, grab a grade sheet dedicated to BELLWORK™ and get yourself ready for each student to come see you privately to announce his score. Although this takes time to accomplish, it's relatively easy to do. And the fact that you're talking to one student at a time allows for a bit of privacy in the sharing of information.

Concern: What the heck do they do after they've seen you? Without direction, you're looking at a bit of chaos.

The simple solution is to have something for them to do independently. They could read, take a look at the pages for that day's lesson, or get their homework ready to be checked or collected. Whatever you have them do, make sure you have a way to document the students who are not doing what they should be doing. And since you have the BELLWORK™ grade sheet out anyway, why not use that? A simple minus mark in the student's box would work. After x number of minus marks, you could see the student privately and ask why he needs to be reminded about doing the right thing.

Oral Report

Similar to the Personal Visit--but without the tedium of them coming to see you--is the strategy of collecting scores orally. Since my students were numbered, the entire process was easy to do.

Mr. Morris

Wtih grade sheet and pencil ready:

Collecting scores!

A slight pause and then:

#1Amanda

Ready with her score since she knows she always the first to report:

Four.

And with the first score announced, we were off and running with each student announcing his score without the need for me to call out the student's number. Granted, it took a couple of weeks for this routine to become automatic; nonetheless, once they had had a chance to practice this procedure, the scores began to fly onto my grade sheet.

Concern: What about privacy and the fact that some students are going to have to announce a low score in front of their peers?

The simple solution is allow each student the option of seeing you privately as scores are being announced. The only requirement I had was that the student needed to be at my desk before it was his turn to provide the score. Otherwise, you'll find yourself wasting time because student #19 is waiting for student #18 to announce his score befores he begins his journey to your desk. Yikes.

For the record: With each new class, I took a moment to point out that just because a student was coming to share his score privately didn't mean he had a low score. When asked to provide reasons why someone with a high score would come see me, they always came up with a number of reasons. The student is just a private person or he doesn't want to be teased for being so smart of he just likes to get out of his seat. Whatever the reason, the issue of seeing me privately became a non-issue.

If you want to make the collection of scores both easy and quick, you might have to let go of getting everyone's score for every assignment.

If you want to make the collection of scores both easy and quick, you might have to let go of getting everyone's score for every assignment.

Collect Nothing

The easiest collection method is to not collect scores at all. In fact, you might just be thinking that having your students do the BELLWORK™ assignment and then correcting it with them is enough. The collection of scores is not critical to the success of your students. And, besides, who has time to collect scores anyway?

Yeah, but...

Concern: How long do you think your students will make an effort to do their best if they know you're never going to check to see how they did? Something else to ponder is this:

Sampling

Although it may seem odd, collecting just a handful of scores each day is not a bad way to go. Done over a period of time, sampling will provide you with a fair approximation of how each student is doing with BELLWORK™. And even though the assessment won't be as accurate as if you had recorded the score for each assignment, the rough estimate will suffice quite well. After all, this isn't a SAT result. It's just a short "let's get the day started on-task" kind of thing.

Concern: How accurate are the scores you're collecting. After all, you're having to trust that the student was honest during the correction process. But, then again, that's the case with however you collect scores.

Collecting a score from every student for each assignment can be done quickly but it's going to take some effort on your part.

Collecting a score from every student for each assignment can be done quickly but it's going to take some effort on your part.

Gather the Work

Skip the correcting process and procede directly to gathering their work. Later on, when you've got a moment, you can check how they did and record their scores.

Concern: How long you last using this method before you give up.

Have the Students Do It

After correcting the assignment, the students--working in group--will record their scores on a piece of paper. These papers are collected from each group so that the scores can be transfered to a grade sheet.

Concern: Once again, we're having to trust students to do an accurate, honest job of self-correcting. You could, of course, have them switch papers within their group before correcting but that strategy always brings with it a couple of problems.

For one, there's a feeling on their part that you don't trust them to be honest. And although this won't be a spoken statement, it comes through loud and clear. The other issue is one of privacy. A student who doesn't normally do well on BELLWORK™ isn't going to appreciate the fact that his poor performance is being made clear to the students in his group.

![]()

BTW: If you have your own slick method for collecting scores, please let us know. Send me an email, and I'll add your suggestion below.

![]()

A friend of mine shared this idea with me for a different reason but I have used it to record scores. I provide each student a laminated poster paper and a dry erase marker with eraser on one end. It's kind of like a personal whiteboard but not as expensive. (My friend actually bought a tile piece from a hardware store cut to size instead of the laminated paper.)

After the BELLWORK™ has been checked, I ask them to write their score on the upper right hand corner of their "whiteboards." When I call their names--although I'm thinking about switching to calling their numbers--they show me their paper with their score.

Note: There is always somebody who wants to take a look at somebody else's score. I gave earlier instructions for everyone to "mind their own business". Or should I say "mind their own score".

WHAT IS BELLWORK™?

Originally conceived and brought into the classroom in 1949, BELLWORK™ has evolved into a successful program of daily, systematic, and structured distributed skills practice and is having a significant impact upon student achievement. In fact, schools in California using BELLWORK™ score an average of 233% higher on API Growth than the California State Average. (2007 results)

The name itself is a reminder to students that "each day (or period) begins at the bell." And the absolutely best way for students to begin is with some type of activity that requires them to be academically on-task. Whether the task to be completed is contained in a student book or being projected on a screen for everyone to see, the daily practice BELLWORK™ provides enables students to improve their understanding and mastery of important content standards.

If you've never tried BELLWORK™, you owe it to your students to take a closer look. A visit to their website will enable you to download some sample activities so that you can give it a try. Based upon my years of using it, I can almost guarantee you're going to wonder how you ever got your day started without BELLWORK™.